"Dysinfluence" - from Dys, meaning harmful, and influence - examines a critical evolution in digital manipulation - the strategic exploitation of influence systems to shape not just what people believe, but how they come to believe it. Dysinfluence functions through multiple mechanisms that undermine factual discourse and knowledge production. Within the age of dysinfluence, the norms of factual discourse are undermined by deliberate contrarianism, manufactured controversy, false equivalence, or an insistence on treating falsehoods as equally valid to credible reporting. This is reinforced by disingenuous influence, which launders falsehoods under the guise of inquiry—framing misleading narratives as open-ended questions rather than direct claims, making them harder to challenge. Meanwhile, dissuasion targets institutions of knowledge, seeking to discredit scientific, journalistic, and historical expertise, often by portraying them as biased or compromised. Digital platforms amplify these dynamics, as disproportionate influence ensures that sensationalist, emotionally charged, or outright misleading content spreads further than sober analysis, often drowning out more reliable sources. Certain individuals and corporations, such as Elon Musk, hold disproportionate influence in manipulating digital spaces and mediating reality. The spread of distrust in institutions, academics, experts, and government further amplifies these effects.

Dysinfluence is used by a range of actors, from state-sponsored propaganda networks to ideological influencers and commercial interests. It can manifest in many forms, including astroturfed campaigns, algorithmically boosted narratives, and deepfake content designed to manipulate perception. Regardless of the method, the outcome is the same: an increasingly fragmented information space where claims are endlessly contested, expertise is devalued, and uncertainty is leveraged as a political or economic tool. In such an environment, truth does not disappear entirely but becomes just one of many competing narratives, leaving individuals to navigate a landscape where credibility is subjective and verification is increasingly difficult.

Dysinfluence is not simply an extension of information disorder; it is deeply entangled with broader shifts in digitality, power, and the restructuring of influence in contemporary media ecosystems. Unlike traditional models of propaganda or state-controlled information flows, dysinfluence operates within a decentralized, platform-driven, and algorithmically amplified attention economy. It thrives in an environment where visibility, engagement, and controversy are the currency of influence, rather than credibility, expertise, or factual integrity. This makes dysinfluence not just a phenomenon of misinformation but a structural feature of how power is exercised in the digital sphere—where those who control the flows of engagement shape reality itself. Dysinfluence ‘supply chains’ point transnational economic flows of supply and demand for falsehoods or harmful information, with PR companies, governments, and big tech key nodes in this network. Intent to spread false or harmful information is less important, but structural motivations for dissemination of content, often wrapped in disingenuous claims of protecting free speech, oil the the wheels of dysinfluence. It’s not the free speech is important, but speech is free that is important.

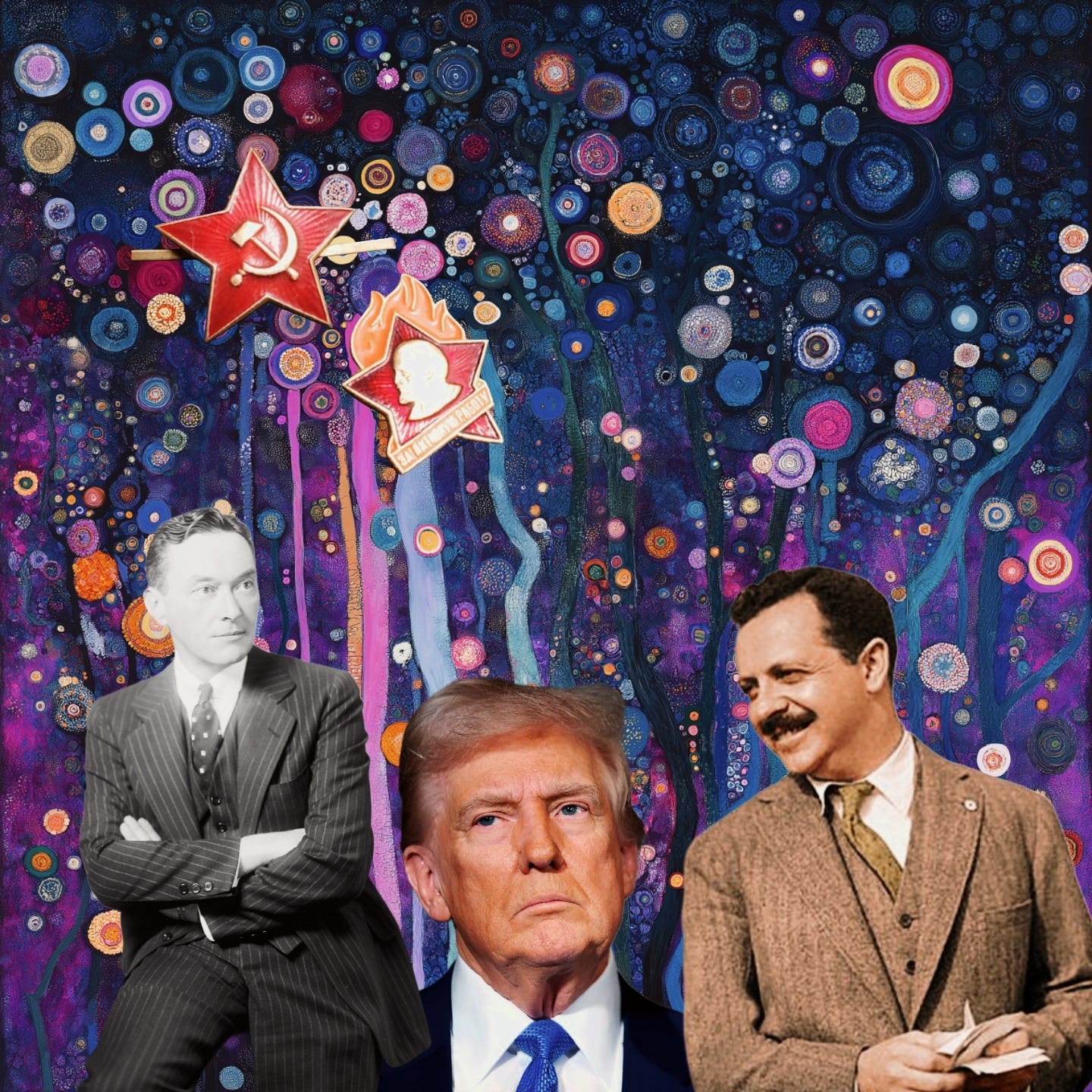

The rise of dysinfluence parallels the rise of influencers as dominant nodes of information production and distribution. In an era where institutions such as journalism, academia, and governance are no longer gatekeepers of knowledge, influence has shifted to a new class of actors who gain legitimacy not through expertise but through reach, engagement, and the ability to command audiences. These dysinfluencers (routine spreaders of harmful often false information)—whether political operatives, media personalities, state-sponsored accounts, or algorithmically amplified agitators—do not need to convince people of a singular alternative truth; they only need to create the conditions where truth itself is destabilized. Unlike earlier models of propaganda that relied on centralized messaging, dysinfluence flourishes through polycentric networks of influence, where multiple actors contribute to an ongoing process of epistemic corrosion for money, power, or ignorance. The digital architecture of platforms like X, TikTok, and YouTube further exacerbates this process by rewarding virality over verification, malice over beneficence, ensuring that content designed to provoke and disrupt outperforms content designed to inform.

At its core, dysinfluence reflects a broader transformation in the ownership and control of information. Historically, knowledge production was largely tied to institutions that exercised editorial control, from news organizations to academic bodies. The digital age has fragmented this control, redistributing epistemic authority to individuals, networks, and opaque platform algorithms that optimize for profit rather than accuracy. In this landscape, dysinfluence is not just an aberration or an abuse of digital systems—it is an emergent property of how information circulates under increasingly authoritarianism, democratic backsliding, and platform capitalism.

The key issue is not simply who is telling the truth, but who owns the means of truth production and who benefits from the collapse of shared reality. By examining dysinfluence through the lens of digitality, influence, and ownership, it becomes clear that it is not merely a problem of bad actors but a reflection of deeper shifts in power—where the battle over knowledge is fought not in the realm of facts alone, but in the infrastructures that determine what counts as knowledge in the first place.

These reflections are not comprehensive, but I will add to them as I flesh out the concept.

This is an excellent unpacking of what feels like the natural end-state of Web 2.0 - an era that promised democratised voices but delivered algorithmic chaos. Dysinfluence captures the structural nature of this better than "disinformation" ever could.

What you describe feels like the inevitable outcome of an unregulated attention economy, where visibility and virality replaced credibility and accuracy. The architecture of Web 2.0 wasn't designed to promote truth - it was designed to promote engagement. Dysinfluence is what happens when those incentives mature.